Mon 8 Oct, 2012

A slave trading family on NBC’s “The Office”

Comment now Filed under: HistoryTags: James DeWolf, Legacy of slavery, Slave trade, The Office, Traces of the Trade

While I usually blog at the Tracing Center these days, I thought this post I wrote today might be worth sharing with readers here, too. Please feel free to offer any thoughts below, or comment here.

While I usually blog at the Tracing Center these days, I thought this post I wrote today might be worth sharing with readers here, too. Please feel free to offer any thoughts below, or comment here.

When I sat down this weekend to watch last Thursday’s episode of “The Office,” I was quite surprised to discover that the plot largely revolved around the revelation that Andy Bernard, like me, is descended from slave traders.

As you might imagine, as someone who has wrestled with this family legacy, and who cares a great deal about seeing the public to terms with the legacy of slavery, I had mixed feelings watching this subject being addressed in a half-hour comedy show.

What did “The Office” get right?

What do I think the show got right about Andy’s suspicion that he was descended from slave owners, and his eventual discovery that his family were slave traders? Mostly the incredible awkwardness and uncertainty, for Andy, his family, and for everyone else witnessing the process of uncovering the truth about complicity in slavery.

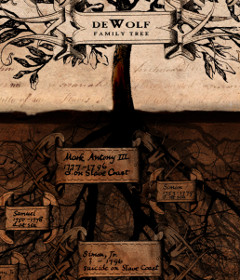

When I first learned that I’m descended from James DeWolf, the nation’s leading slave trader, and during filming of our PBS documentary, Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North, I wrestled with powerful emotions and with how to understand my family’s legacy today. I remember struggling to decide how this family history, and its undeniable effect on my life today, does and does not matter for my own sense of self and for my place in the world. Other DeWolf family members experienced similar awkwardness and uncertainty, although the details varied: some openly addressed feelings of guilt and shame, while others worried about how their black friends and colleagues would view them after this revelation. Bystanders, including our own production crew, inevitably found themselves uncertain how to relate to this history, and to us, which led to many awkward moments during filming.

“The Office” derives much of its comic genius, of course, from milking the awkwardness inherent in addressing serious subjects in a lighthearted way. In this case, I think that this discomfort, both for the show’s characters and for the home audience, accurately reflects how painful and unresolved this history remains, and how little our society has figured out what to make of our deep and varied ties to this dark past.

The episode also reveals other common reactions to a family history of slavery that demonstrate how little our nation has healed from this history. In fact, Andy rapidly moves through a series of responses, vaguely reminiscent of the classic five stages of grief; in this case, his behaviors include denying the truth (literally ending a conversation with “I don’t want to know that”), minimizing the historical wrong, denying its relevance to him (“it’s not our fault, so we don’t have to talk about it”), and seeking validation by emphasizing his ties to black people and culture today.

Finally, when Andy tries deflecting the focus from his family, by suggesting that his coworkers, too, may have family ties to historical wrongs, Oscar appropriately chastises him by making the following distinction:

You’re the only one here still benefiting from the terrible things your ancestors did.

In a way, Oscar is right. In my work, I frequently encounter white people who try to dismiss the history of slavery, and the benefits they continue to receive from this history, with the observation that we can find many historical wrongs if we look far enough into the past. The difference is that most historical wrongs have dissipated over time: their effects don’t continue to harm millions of our fellow citizens, while systematically benefiting millions of others.

(However, please read down to the end of this essay, where I explain that Oscar’s statement is also terribly wrong.)

What did “The Office” get wrong?

What, then, did the show get wrong about the history of slavery and about family connections to it? Plenty, I’m afraid.

Let’s start with the initial claim, which turned out to be false, that Andy is distantly related to Michelle Obama. In itself, this is entirely plausible, and the fact that Andy is white, and Michelle Obama black, doesn’t change how common such ancestral connections are.

The problem here is that Andy’s coworkers immediately leaped to the conclusion that Andy’s family were probably slave-owners. Historically, there were many ways in which white and black people had children together. Certainly, there were often abusive sexual relations between slave masters, or members of their families, and black slaves. But there were also sexual relationships between other free white people and black slaves, and sexual encounters or marriage between free white and free black people, throughout the nation’s history.

This summer, for instance, Ancestry.com announced that President Obama is likely descended from John Punch, the first documented American slave, through the president’s white mother. The reason? Records suggest Punch, although not free, nevertheless fathered children with a white woman. These children were considered free and, in time, their descendants became known as wealthy white Virginia landowners.

So genealogical connections between black and white families in this country, stretching back as many as four centuries, are quite common and it would be a mistake to assume they’re all the result of liaisons between slaves and slave masters.

Why else did Andy’s coworkers immediately suspect that his family connection to the First Lady meant that the Bernards were probably slave owners? The fact that Andy comes from wealth. Yet most slave owners were not particularly wealthy. Many southern families of more modest means owned slaves, and especially in the North, it was quite common for white families in the middle class to own just one, two, or three slaves.

This misconception about the nature of American slavery only becomes worse as the episode progresses. As Andy attempts to sort out his family history, he asks his mother this question (and only this question):

Did any Bernards own a plantation in the South?

His mother says they did not, and Andy, relieved, believes that he has ruled out slave-owning in his family tree. Yet this assumes that slavery was the sole province of southern plantation owners. In fact, while southern slavery did generally follow a plantation model, this hardly meant that all southern slaves were kept on plantations. More importantly, many slaves were owned in the North, where there were few plantations, and northern blacks were generally enslaved in ones, twos, or threes to work in coastal cities or towns or on small family farms.

Then, when Andy finally learns the truth about his family’s connection to slavery, he announces to the office:

We merely transported them … which at worst makes us amoral middlemen.

This is a fascinating distinction to make, especially for someone like me, whose ancestors were notorious slave traders.

Let’s leave aside the fact that slave traders certainly did own slaves, even if they often owned them only while transporting them (which in the case of the transatlantic slave trade, meant controlling the lives of enslaved Africans for months at sea, in the most brutal conditions imaginable). Let’s also ignore the fact that many slave traders, like my DeWolf ancestors, also made money by owning and working slaves directly.

What does it mean to have “merely” transported those who were enslaved? If it is immoral to enslave people and sell them to passing ship captains, and to work slaves on southern plantations and in northern homes, how it is merely “amoral” to purchase the enslaved and transport them to auction?

Andy’s dismissive line is, of course, meant mockingly, and Ed Helms does a great job of portraying someone in denial about the reality of what he is saying. Yet I don’t remember anyone, in the thirteen years I’ve been speaking publicly about this issue, suggesting for even a moment that slave trading doesn’t raise the same moral issues that slave owning does.

Most importantly, who really benefits from slavery?

Finally, I promised that I would explain what is wrong about Oscar’s observation to Andy that, unlike those whose families were involved in other historical misdeeds:

You’re the only one here still benefiting from the terrible things your ancestors did.

It’s true that Andy still benefits, as Oscar says, from the terrible things his slave-trading ancestors did. Yet he’s far from the only one in the room for which this is true.

All white families in this country during slavery were complicit in that institution, and benefited from it. This applies to the many, many families that owned one or more enslaved black people, whether in the North or the South, or in many cases, in the Midwest or the West, too. This applies to those families, like my own, which profited by engaging in the slave trade. It also applies families which knowingly benefited from economic connections to slavery or the slave trade, including those from throughout the Northeast who supplied goods for slaving voyages, those in the South who made a living based on plantation slavery and the wealth it generated, and those in the North who financed, insured, and provisioned southern slave plantations and marketed, transported, and sold the cotton and other goods produced.

This complicity in slavery even applies, for example, to those families which moved into the Midwest and the West to establish family farms, as that migration and economic activity was driven primarily by the insatiable demand for foodstuffs to be exported to the Deep South to feed four million enslaved laborers on cotton plantations.

What about those in “The Office” whose families might have arrived in this country after slavery ended in 1865? Their immigrant families might not have been directly complicit in slavery, but European immigrants in the 19th and early 20th centuries came to these shores primarily because there were plentiful jobs to be found. These jobs existed largely because of the wealth that had been generated over centuries by slavery, north and south, and by the industrialization made possible by slavery. Moreover, these immigrants and their descendants prospered because of those jobs and a booming industrial economy, and as long as they worked hard to get ahead, they were able to better their lives through access to job advancement, education and housing that were, at least until quite recently, denied to the descendents of the nation’s slaves.

These immigrant families, like those of us living in this society today, were not complicit in slavery itself, and did not ask to live in a society in which white people benefit, and non-white people are harmed, from the lingering social, economic, and institutional effects of slavery and racial discrimination. Nevertheless, they, and each of us today, in varying degrees, have benefited from the terrible things that Andy Bernard’s ancestors, and my own, did during the time of slavery.