Tue 10 Feb, 2009

PETA uses white supremacy for animal rights

Comments (30) Filed under: Thinking about race, privilege and inequality| Tags: Animal rights, PETA, Racism, Sexism, Slavery |

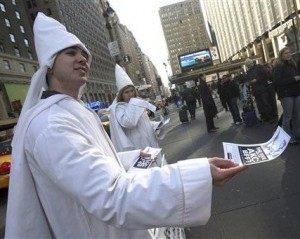

The latest animal-rights campaign by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) involves PETA members dressed as the Ku Klux Klan to dramatize the abuse of animals through breeding for profit.

The latest animal-rights campaign by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) involves PETA members dressed as the Ku Klux Klan to dramatize the abuse of animals through breeding for profit.

PETA was demonstrating outside the Westminster Kennel Club’s dog show in Madison Square Garden, in a protest against the American Kennel Club (AKC), which PETA accuses of promoting the pure-breeding of dogs to the detriment of their health.

PETA has a long history of sensational and controversial publicity campaigns to draw attention to the plight of animals, which frequently bring charges of sexism, racism, or poor taste. In a 2005 campaign, for instance, PETA contrasted images of lynched black men with pictures of dead cows and asked, “Are Animals the New Slaves?”